Just the facts?

At a recent conference, Kim was speaking to a room full of people who live and breathe data. Her talk was about effective communication in a polarized world, and she centered it around three ideas:

- We remember people and their stories—especially authentic stories of struggle and triumph—far more than we remember numbers.

- We still need data to establish credibility and logic.

- But it’s the emotional appeal that makes the numbers meaningful—and ultimately stirs people to think, feel, and act differently.

Anyone who’s been following along here knows this premise is the foundation of our work at Right On.The dots connect directly. Or so we thought.

That night during a walk to dinner, we ended up chatting with a data scientist who had heard Kim’s talk and raised an interesting point: she said storytelling made her uncomfortable. That using stories to present information felt… untruthful. Inaccurate. Like she was making things up.

Her comment surprised me. But considering our audience, it probably shouldn’t have. It also surfaced something we see often in sustainability, and especially at the intersection of sustainability and healthcare: a belief that data equals truth, and that storytelling somehow compromises it.

Of course, I respectfully disagree. And I’ve got the data to prove it, so let me tell you a few stories.

The truth about stories

I have strong feelings about the importance of storytelling because our work proves that a good story isn’t the fluffy counterpart to accuracy. And it doesn’t distort the facts. Effective storytelling reveals facts in a way that lights up the brain to prompt not only a feeling but also a response.

That’s why Dr. Sarah Goodwin, Executive Director of the Science Communication Lab, and her team use short, documentary-style videos to communicate scientific information and show the human side of the scientific process. And she’s done the research to back this up. She recently told the NIH Record, “Stories have been shown to enable audiences to take in new information more quickly and easily and retain that information.”

In the video below, Hawaiian microbiologist Kiana Frank takes us to a sacred fish pond and explains how traditional knowledge and microbiology can work together to help us understand how to care for and manage the land.

For most scientists, this isn’t the go-to approach. And maybe that’s what our friend from the conference was struggling with: her natural instinct to lean into traditional articles, journals, and lectures rather than harness the power of storytelling to inspire human connection and bring her critical research to life. At Right On, we know that data is essential for effective storytelling. We’ve written a lot about it. It offers proof and establishes credibility. But data alone is only one dimension of truth. While it may tell us what happened, it rarely tell us why it matters, who it affects, or what comes next.

Stories are how humans make meaning from information.

They’re how we connect cause and effect.

They’re how we remember.

They’re how we decide what action to take next.

Science-y subjects strengthened by stories

⇒ Do you know what glyphosates are? I knew they were bad but really didn’t know how they affect me (they’re everywhere, from food to water to medical gauze), why I should care (causes cancer), or what to do about it (regenerative farming practices). Farmer’s Footprint has taken to video, podcasts and social media to get the word out. And while the scientific research runs deep and the data is damning, it’s their use of beautiful, simple stories that connects people to the problem and makes us care.

Farmer’s Footprint uses storytelling of all varieties, like this lovely montage of farmers that lives on their website and YouTube.

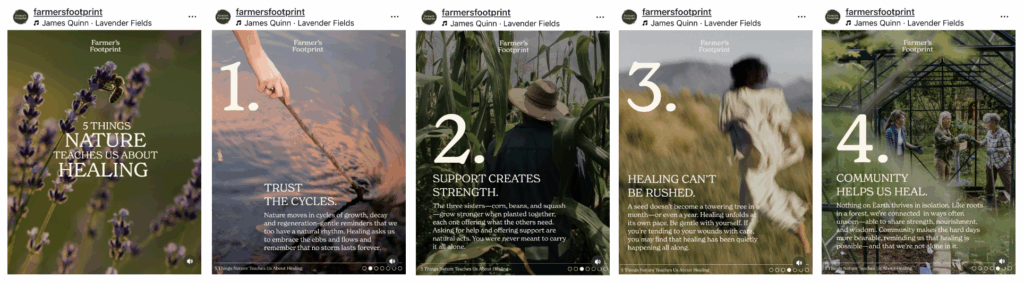

Or these simple social posts that sequence out the essential connection between planetary health and human health.

From these storytelling entry-points, we can go deeper to better understand the role that glyphosates are playing in negatively impacting our environment and our health.

⇒ Have you ever heard of Leavenworthia Crassa or Leafy Prairie Clover? Me neither until recently thanks to Kyle Lybarger of Instagram fame and his Native Habitat Project. These rare wildflower species are endangered, and Kyle’s armed with facts to support that truth. But he would rather show you the delicate blossom while standing in the middle of a wide-open prairie as he excitedly preaches about their reason for being.

His southern drawl is soothing. His passion palpable. His knowledge vast. And his use of personal storytelling is the definition of authentic. Altogether, it’s all how he’s getting people to care about saving native habitats and native plants in North Alabama. And these simple, yet powerful explanations of the significance of specific species within our prairie lands is garnering the attention and action of conservationists, hunters, NYC Climate Week organizers, developers, and corporate giants.

These species were endangered before Kyle got involved, but bringing them to life with a story is what might just save them.

The goal isn’t to choose between facts and feelings

Whether it’s healthcare informatics, climate science, or corporate sustainability, you could conduct years of research, crank out a fact-filled paper or report, and still fail to change a single mind. For data-driven fields, or really any field for that matter, we’ve got to make abstract concepts tangible through:

- stories rooted in real experience,

- supported by relatable examples,

- told by human voices

End of story.

Our Most Recent Insights.

SEE ALL INSIGHTS →

Strategy

How to talk climate with conservatives.

Many conservatives care deeply about the environment. They just talk about it differently.

Storytelling

Stories of hope from Climate Week.

At Climate Week NYC, people showed up with creative, courageous climate solutions.

Strategy

Get your sustainability initiatives funded.

How healthcare leaders win support for sustainability — and how you can, too.